Practice: Semantic Mapping

For finding the world within and without human terms

Semantics is difficult, because unlike phonetic substance, semantic substance cannot be measured or observed objectively (Martin Haspelmath, 2003).

A god who could be proved by us would be an idol (Dietrich Bonhoeffer, DBWE 11:260).

I refer to “semantic maps” often when talking about etymologies and conceptual structures. The notion of a semantic “map” can be a really interesting one for applied semantics, since it points to multiple layers of map-territory relation:

Language is a map or model of intersubjective reality, but…

We develop and manage that map pretty implicitly and unconsciously, meaning that…

For metalinguistic discourse, we have to make maps or models for how language works. Hence…

The map is its own territory.

This idea of semantic mapping — very loosely or colloquially defined as mapping meaning relationships — is used in a lot of different domains, applied contexts, and fields of study, so it’s worth defining what it means in a linguistics context versus other contexts, and why the linguistic-y version can be relevant in an applied context in ways that are different from other kinds of “semantic maps”.

I’ll start by giving an overview of how the idea is used in other domains, and then get to semantic mapping proper in the context of linguistics. I will probably then jump the shark and think about how to use semantic maps to escape samsara. 🧘🏼♂️

Visual Learning Device in Education

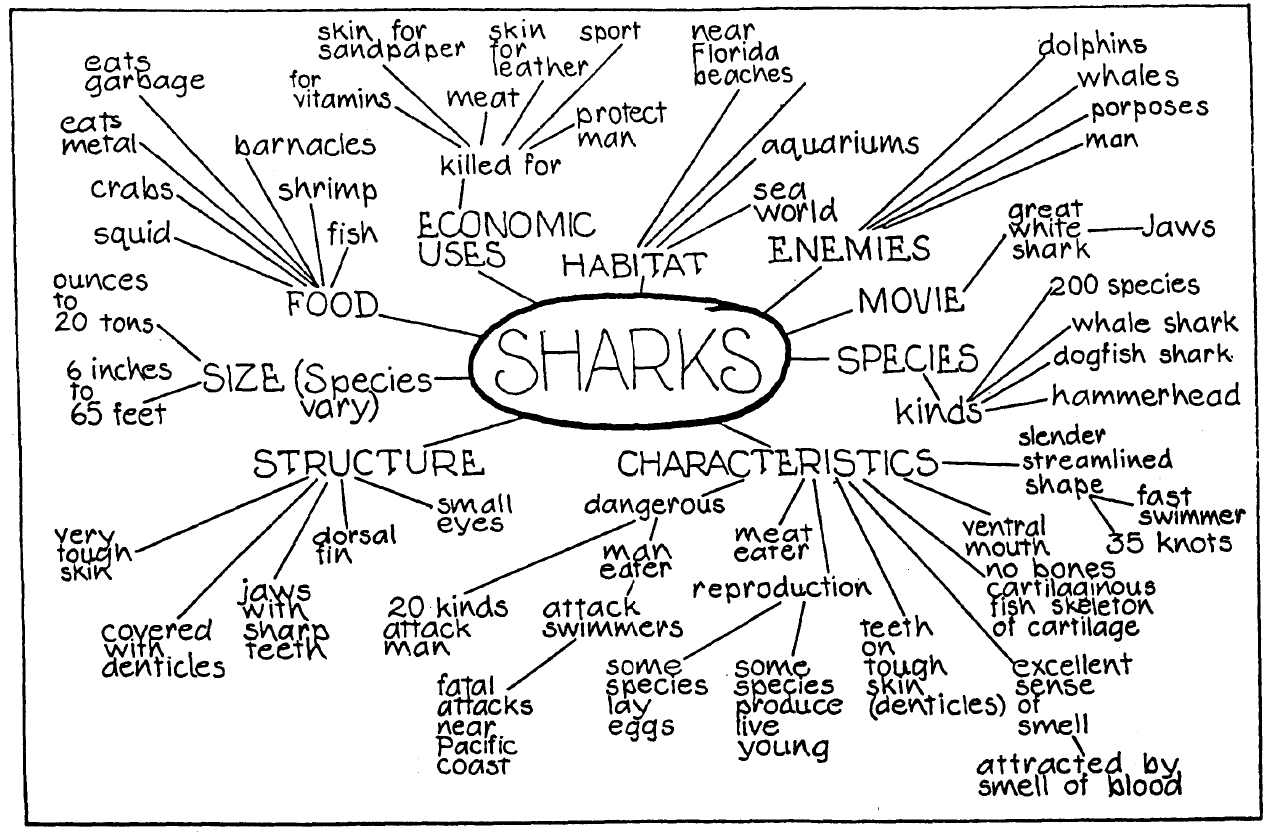

“Semantic map” is one name, kind of a more technical one, for something that you probably did a lot of in school if you were born after like 1980 — you might have called it a concept map or a bubble map or a word map. It’s this thing:

This kind of semantic map is definitionally the map image [it is useful to be able to distinguish between the representation of relationships and the web of conceptual relationships itself]. This is a learning device, first and foremost, originally and still primarily promoted as a vocabulary builder, reinforcing knowledge of terms through creating a visual stimulus that links vocabulary items. It is hierarchical and oriented around defining the semantic domains of a set of concepts in relation to a top-level domain concept.

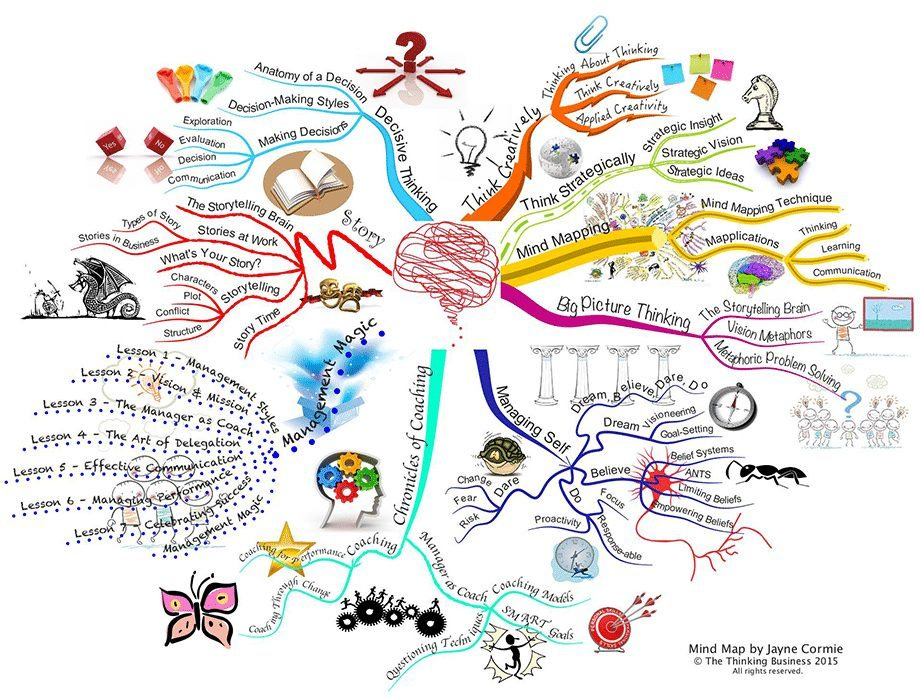

A similar kind of semantic map is the mind map. There are some arguments about what should be considered a meaningful difference between a concept map and a mind map, but the primary distinctions is that one is heirarchical in its organization and the other is not. Which one is which is apparently not agreed upon in the least. Also, mind maps conventionally use pictures. The latter point probably makes them a step closer to the representation of meaning in the mind, since sensory, emotive, and other experiential information grounds conceptualization beyond simple patterned word association.

Marketing and Consumer Research

A concept map or mind map can be used both for creation and discovery of webs of meaning. The learning device kind of map is more about creating something, helping you to establish a web of meanings that can make it easier to absorb new information. You can also use this technique in a more descriptive fashion, creating concept maps to describe and define.

Using concept mapping to discover implicit webs of meaning in an individual or (more often) a given population is a pretty common process in a lot of different kinds of qualitative research conducted for all kinds of purposes. In an applied sense, if you want to direct behavior in some way (like get somebody to buy something, or vote for one candidate versus another), you might do that by leveraging what you know about their assumptions.

I kind of assume that the purposes of this kind of concept mapping and the associated research — identifying consumer trends, sentiments, and beliefs —are transparent enough. Selling shit is kind of our whole culture so… But I think this pull from Culter and Zaltman (1994) sums it up pretty well:

Because a firm's or ad agency's metaphors about a brand are conveyed in the form of various marketing mix decisions, including advertising, product and package design, product concepts, and distribution channels, these metaphors need to contain components that are both similar and dissimilar to their customers' metaphors. The similarities are necessary because customers are predisposed to find their own metaphors in advertising, the design of a product, or a store setting, for example. Thus, when marketer communications are congruent with customer-generated images, customers are more likely to attend to, process, and comprehend the observed information. The dissimilarities are also necessary; they create a degree of tension that attracts attention and sets the foundation for message comprehension. Creative staffs and product design staffs play a particularly important role in providing the creative "dissimilarities" component.

The methods and techniques are a little different than the elementary school concept bubble map, however. One popular one known as the Zaltman Metaphor Elicitation Technique (ZMET) begins with defining a research topic and then getting research participants to collect images that metaphorically represent their thoughts on the topic. One-on-one interviews follow, during which participants explain their image choices, revealing underlying metaphors. Participants then create visual collages to map their metaphors, and researchers identify themes (like… words) from these maps, developing a consensus map that represents collective impressions. There’s some quantitative analysis involved in measuring the frequency of different connections and metaphors in the participant group, but that’s the gist of the approach.

What’s interesting and important about the techniques used for this kind of concept mapping is that the researchers don’t assume that they can just ask participants what their maps look like — part of the premise is that the average person has relatively little conscious awareness of their own metaphorical maps for interpretation. You have to find multiple avenues for the connections to emerge and be recognized.

Machine Learning, AI

We are certainly in the midst of a paradigm shift regarding our understanding of how meaning in language works — for better or worse, a lot of folks will assume that the way the AI machines and LLMs that we build learn and structure language is the same as what we humans do, especially once the surface output is indistinguishable from humans. There’s probably some limitations to this approach, but there’s probably some valuable truth — we will certainly come to a better understanding of the role of analogy in language development.

One conceptual development specifically related to this idea of a concept map is the idea that categories or concepts are formed on the basis of connections. When we draw out one of those bubble maps, we kind of start with the bubbles and then make the connections, but the progress of machine learning is giving a lot of support to the idea that the connections come first and the categories or concepts emerge as a product of the connections.

The sign, the word, constitutes something of a discrete node, but the meanings that the signs attach to are emergent through connection — there are no base semantic primes.

The Semantic Map in Linguistics

The concept of semantic map that has emerged in linguistics, especially in the context of lexico-semantic typology in the last couple of decades, is based on the idea that any individual word in any language has numerous use cases (i.e. semantic or grammatical values) and therefore languages will group together different sets of use cases using their lexicon (a.k.a. vocabulary).

The color thing, where languages carve up the same range of visible light values into different categories, is a basic example of this. But… we kind of do this with literally everything.

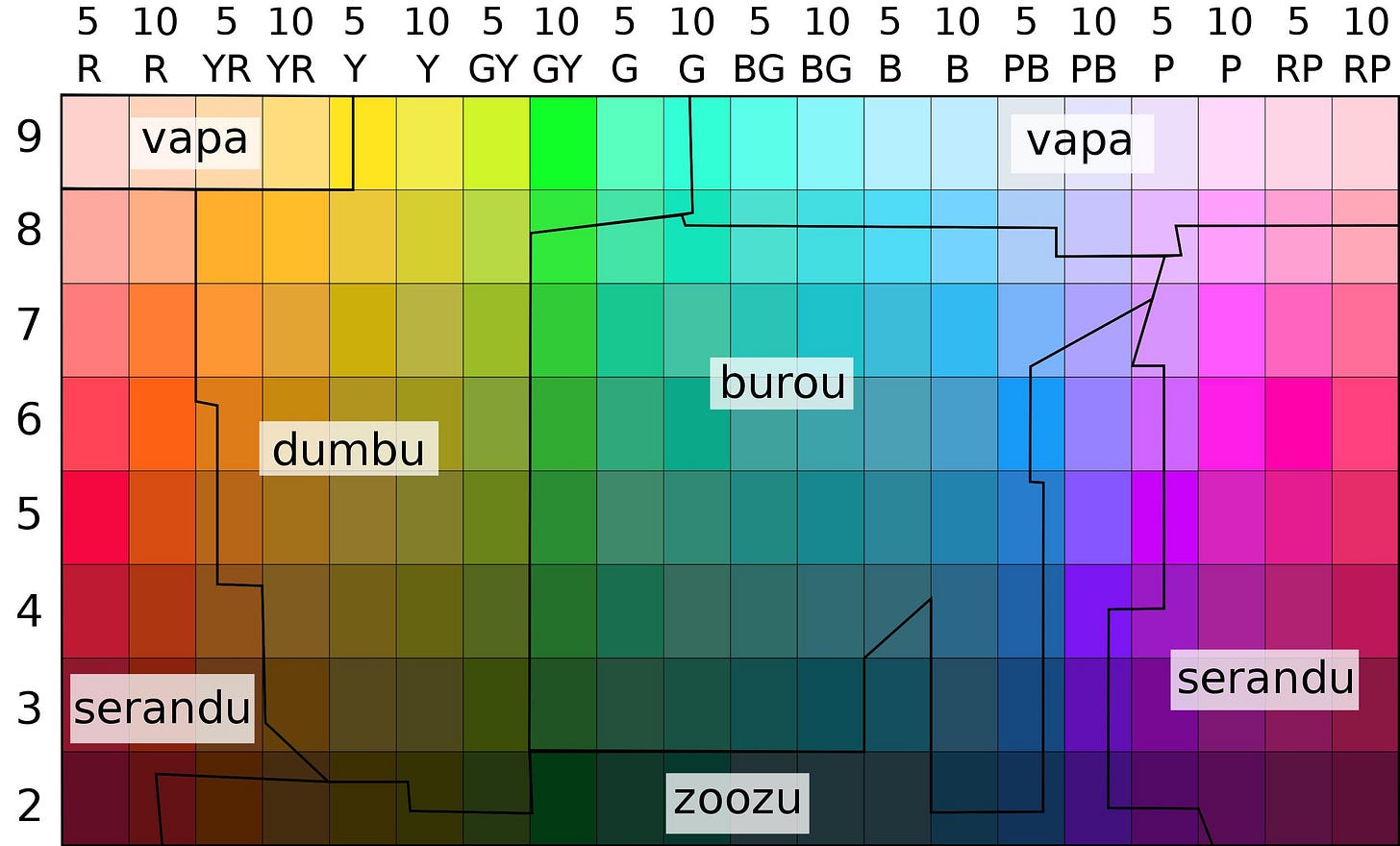

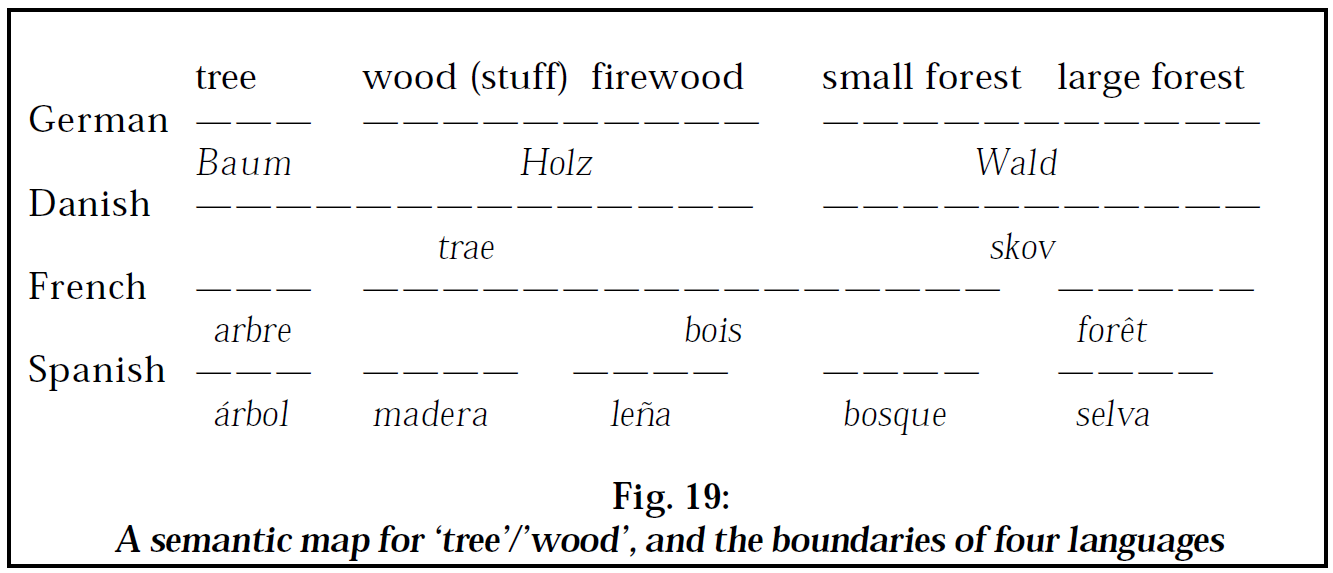

I’ll give you the example that gets repeated a lot in linguistic publications on semantic mapping. In the image below, we have a map of the semantic scope of words relating to trees in four European languages (all related, no less). The top line shows five concepts represented in English — ‘tree’, ‘wood, like the material’, ‘firewood’, ‘a small forest’, and ‘a large forest’.

What we are looking at with the semantic map is how these different concepts are packaged into single words in the various languages under comparison. So, Spanish happens to be the most lexically maximalist here, having a totally unique word for each of these five meanings. Compare that with Danish, which only has two words across the five meanings. What Spanish speakers would call árbol, madera, and leña would all just be trae in Danish. That Danish trae could be anything from a living tree to a pile of firewood, but if you learned that the Spanish leña translated to Danish trae, and then you tried to go the other direction, you might start speaking Spanish and refer to a living tree growing out of the ground (árbol) as just firewood (leña), which might be a little morbid, like calling a cow a steak.

The relationship between the number of terms and specifity of their meanings is fairly intuitive. It matches the metaphor of carving up a pre-defined space — if you carve up the visible light spectrum into three categories, those categories are going to be a lot bigger than if you carve up the space into eleven or twelve categories. But there’s a more intriguiging point when you start to look at multiple languages, like in the tree map above: languages don’t agree on boundaries.

German, Danish, and Spanish make some different groupings. German and Spanish agree that the living tree and the dead material it produces are different things, while Danish says “living or dead, a trae is a trae”. Spanish then makes a distinction between the dead tree material you burn, leña, and the dead tree material you build with, madera, while German is kind of saying “wood is wood, dude, whatever you use it for”. What all three agree on is that the place with a bunch of living trees (a forest), is a completely different conceptual entity than the organism or the material it yields.

But not the French. In French, bois is both the material (wood) and a small stand of trees. French bois bridges a lexico-semantic gap that the other languages here do not. And, before you go thinking the French are weird, keep in mind that that is exactly what we do in English. I mean, more or less… wood is the material product of a dead tree but there’s also being out in the woods. It’s a bit archaic, but we can also talk about the wood to refer specifically to a small forest. The similarity is generally contact-induced from French to English.

But here is what is important about even a basic semantic map like the tree/wood one above — 1. you can make these kinds of lexical breaks anywhere, and 2. you can only do this kind of analysis by using a base semantic descriptor system (usually in English) that itself can be subject to the same kind of semantic mapping. There is no inherent beginning or end.

Where to go

While more commonly recognized types of concept mapping have clearer use cases — learning and mnemonic devices, exploratory association research — the kind of comparative semantic mapping in linguistic typology is not really used or explored much outside of this specific academic field. However, there are likely a lot of valuable applications for this kind of comparative semantic mapping, even if only from a reassessment of one’s fundamental understanding of how words are associated with entities in the world or concepts in the mind.